Californians overwhelmingly support vaccine mandates in the latest CBS News poll, and there's every reason to believe that Gov. Gavin Newsom will soon make them a reality. The question is whether or not Newsom's recall vote next month will send the Golden State back to GOP control.

As Californians express widespread concern about the Delta variant, they overwhelmingly say the state's recent rise in cases was preventable, had more people gotten vaccinated and taken more precautions.

California's vaccinated voice a lot of judgment toward the unvaccinated: "They're putting people like me at risk" is a top way the fully vaccinated pick to describe those who won't get the shot, with many others outright "upset or angry" with those unwilling to get it. From a policy standpoint, there's strong support for vaccine mandates, too.

Meanwhile, as the effort to recall Governor Gavin Newsom heads into its final month, Newsom faces what looks like a turnout challenge: while voters would marginally prefer to keep him in office at the moment, it looks like that will heavily depend on whether Democrats in his party get more motivated about it.

When California's vaccinated describe people unwilling to get the vaccine, another phrase they select is that "they're being misled by false information," in addition to the emotional response of being upset. Far fewer of the fully vaccinated say they respect the decision of those who won't.

Behind some of those sentiments, we also see that while unvaccinated Californians tend to describe the decision to get the shot as a "personal health choice," the vaccinated are more likely to call it both a personal choice and public health responsibility.

Californians' list of what may have prevented rising cases is dominated by more vaccinations and taking masking precautions, while far fewer point to other measures like more travel and border restrictions. Nor do they cast any blame on scientists and medical professionals for the recent rise in infections. (Though on this, we do see more partisan differences: Republicans are notable for singling out limiting of border crossings as one top way to have prevented it, more so than more vaccinations or policy measures.)

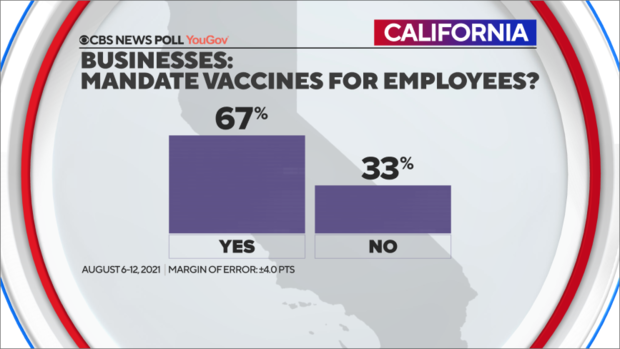

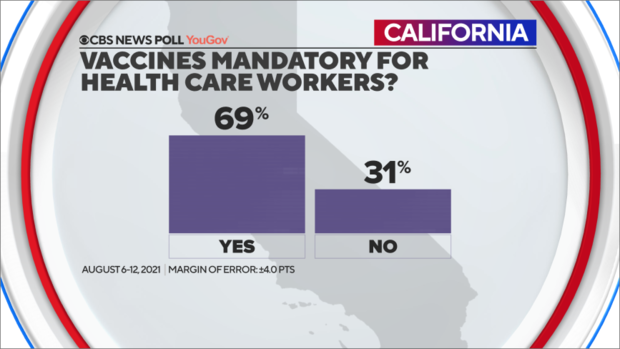

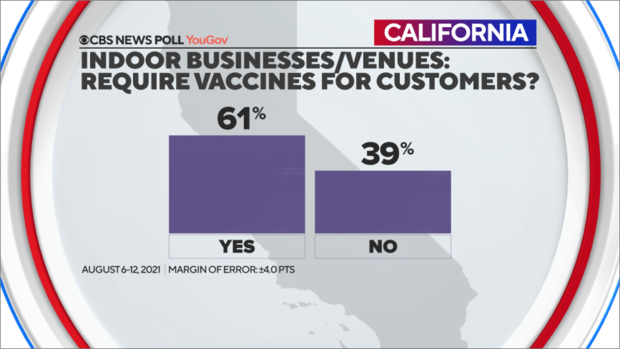

So, given all that, vaccine mandates find wide support across California. A large majority support allowing employers to mandate vaccines for employees. And it's not all that partisan: four in 10 Republicans are OK with this idea, too. There is strong support for making vaccines mandatory for health care workers, and a lot of support for letting businesses that draw crowds also mandate that their customers be vaccinated. Moreover, many people would be more willing to use or visit such a business.

Indeed, we're looking at nearly two-thirds support for vaccine mandates in California. This should be a winner for Newsom in his recall vote, for the people of California to vote NO on recall.

All the GOP candidates have said they will remove all mask ordinances and mandates if they are elected.

Your choice, folks. Make the clearly correct one.